At this stage, all major taxonomic revisions are done. Small database changes may continue for the next several weeks.

We have now completed the process of updating records in eBird. This includes your My eBird lists, range maps, bar charts, region and hotspot lists. Data entry should be behaving normally, but you may notice unexpected species appearing on eBird Alerts as eBirders continue to learn the new taxonomy (this issue will diminish with time). If you still see records appearing in unexpected ways please write to us.

If you use eBird Mobile, we recommend installing pack and app updates immediately as they become available. This will make sure you have the most up-to-date lists for reporting.

Read on for more information about what’s changed. For a complete list of all taxonomic changes, check out the 2023 eBird Taxonomic Update page.

It’s Taxonomy Time!

Our understanding of species is constantly changing. Every year, some species are “split” into two or more, while others are “lumped” from multiple species into one, as we gain a better understanding of the relationships between birds.

“Taxonomy” refers to the classification of living organisms (as species, subspecies, families, etc.) based on their characteristics, distribution, and genetics. There are multiple taxonomies for birds around the globe. Projects at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology—including eBird, Merlin, Birds of the World, and the Macaulay Library—use the Clements Checklist of Birds of the World, or Clements Checklist for short.

The Clements Checklist is updated annually to reflect the latest developments in avian taxonomy. “Taxonomy Time”, as we like to call it, is a time to celebrate, as we get to acknowledge the many scientific advances in ornithology made over the past year (some of them thanks to your eBird data!)

As part of this process, we revisit all 1.5 billion observations in the eBird database and update them to reflect the latest “splits”, “lumps”, additions of new species, changes to scientific names, taxonomic sequence, and more.

Wherever possible, we update your records for you. Not having to worry about name changes or species splits is one of the benefits of being an eBirder. It’s our way of thanking you for contributing to our understanding of bird populations. Thank you! Below are some highlights from this year’s Taxonomy Update.

What to expect in 2023

Our 2023 update includes 3 newly-described species, 124 species gained because of splits, and 16 species lost through lumps, resulting in a net gain of 111 species and a new total of 11,017 species worldwide.

For a complete list of all taxonomic changes, check out the 2023 eBird Taxonomy Update page.

New Species

Three new species are now formally described and recognized this year for the first time; each had previously appeared eBird as an “undescribed form” but will be updated to a full species with the upcoming update: Principe Scops-Owl (Otus bikegila), Wangi-wangi White-eye (Zosterops paruhbesar), and Ibera Seedeater (Sporophila iberaensis).

Meet the Ibera Seedeater

Newly recognized in this year’s taxonomy update, Ibera Seedeater belongs to a group of eight species (and counting!) collectively known as “southern capuchino seedeaters”. These finch-like birds largely overlap in breeding range and are nearly identical on the genetic level, differing almost exlusively in the genes that code for male color and song.

The newly-recognized Ibera Seedeater is the most range-restricted of the group, named after Iberá National Park (Argentina), its only known breeding location. Ibera Seedeater co-occurs with another southern capuchino seedeater—Tawny-bellied Seedeater (Sporophila hypoxantha)—throughout its entire range. However, despite similar genetics and nearly indistinguishable female plumage, these two species are not known to hybridize.

How southern capuchino seedeaters managed to diverge into species while occupying the same space remains a mystery. Recent studies suggest strong female preference for a particular male appearance and song may prevent interbreeding. There is still plenty to learn about the Ibera Seedeater and its close relatives!

Notable Splits

A few species complexes account for a disproportionate share of this year’s splits, with the widespread, familiar Olive-backed Sunbird (Cinnyris jugularis) being split into eight species (!) and Rufous Fantail (Rhipidura rufifrons) being split into six species, along with five-way splits in Hooded Pitta (Pitta sordida) and Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), and four-way splits in Wandering Albatross (Diomedea exulans), Black-throated Trogon (Trogon rufus), Eclectus Parrot (Eclectus roratus), and Fire-breasted Flowerpecker (Dicaeum ignipectus). Learn more about these splits in the 2023 eBird Taxonomy Update.

Five splits this year are worth highlighting because they affect widespread, familiar species and have particularly broad implications across many continents.

- Northern Goshawk is split into Eurasian Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and American Goshawk (Accipiter atrocapillus)

- Lesser Sand-Plover (Charadrius mongolus) is split into Siberian Sand-Plover (Anarhynchus mongolus) and Tibetan Sand-Plover (Anarhynchus atrifrons) [note also the change in genus from Charadrius to Anarhynchus that is taking place this year.]

- Common House-Martin (Delichon urbicum) is split into Western House-Martin (Delichon urbicum) and Siberian House-Martin (Delichon lagopodum)

- Cattle Egret is split into eastern and western populations (the western birds are the ones that colonized the Americas), so birders should get used to Western Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis) and Eastern Cattle Egret (Bubulcus coromandus)

- Intermediate Egret (Ardea intermedia) is being split into three species: Yellow-billed Egret (Ardea brachyrhyncha) of Africa, Medium Egret (Ardea intermedia) distributed broadly in South, Southeast, and East Asia, and Plumed Egret (Ardea plumifera) of Australasia.

All of these have had subspecies groups in eBird for quite some time. Understanding the distribution, field marks, and vocalizations of the various subspecies groups can be a great way to prepare for future splits. Additional details can be found in the 2023 eBird Taxonomy Update.

Reviewing your records for changes

Where splits affect your observations, we will do our best to assign them to the correct new species. However, this is not always possible, and in some cases your records may be updated to a ‘spuh’ (e.g., sand-plover sp.) or ‘slash’ (e.g., Western/Eastern Cattle Egret) instead. See the 2023 eBird Taxonomy Update for a complete list of new ‘slashes’ and ‘spuhs’ added this year.

With the recent improvements around exotic species handling, it is now very easy to see all of your reports of a ‘spuh’ or ‘slash’ under Additional Taxa on your eBird Life List. In addition to reviewing this year’s changes, it may be helpful to revisit your records of meadowlark sp. and Eastern/Chihuahuan Meadowlark to see if any can be refined to the species level following last year’s split of Chihuahuan Meadowlark.

Why did the chicken change to “Domestic type”?

This year we also have an important policy change on Red Junglefowl (Domestic type). Several recent genetics papers (such as 1, 2, and 3) have looked at populations of Red Junglefowl on islands where they are introduced, even places like Hawaii where those introductions happened many centuries ago by Polynesians. These studies reveal more complexity and hybridization than plumage alone might suggest. Even birds that show wild phenotype (smaller and slimmer with gray legs) can be genetically much closer to domesticated chickens than to true wild-type Red Junglefowl.

As a result, we are moving to a policy that treats all Red Junglefowl outside the current native range as Red Junglefowl (Domestic type).

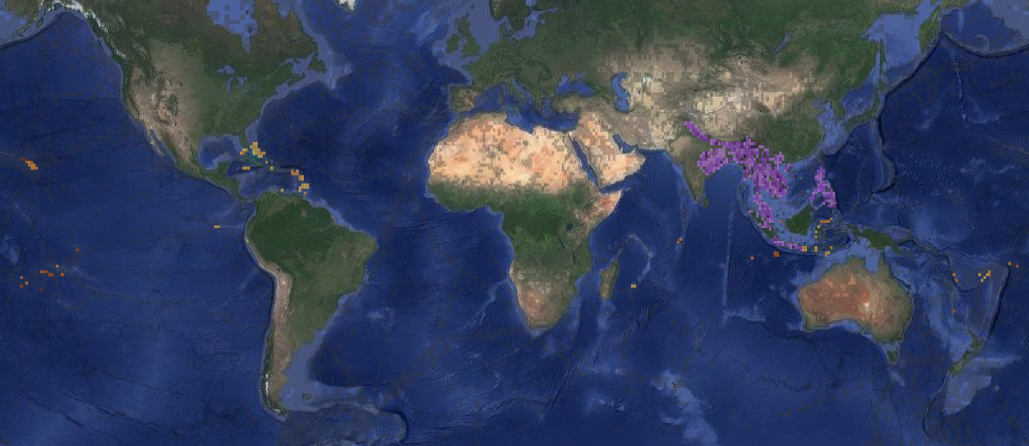

With the 2023 taxonomic update, many of the non-native observations (orange squares) on this map of Red Junglefowl will be converted to Red Junglefowl (Domestic Type).

Observations of Red Junglefowl (Domestic Type) where they are established and breeding in the wild, such as Hawaii—including Kauai, where birds resembling wild-type plumage are especially common—Christmas Island, Tahiti, and more, will be treated as Naturalized Exotic and “count” for your eBird Life List.

This is similar to the policy on Rock Pigeon (Feral Pigeon), which can show domesticated phenotype (white, brown, black, etc.) or wild phenotypes (gray with neat black wing bars and a broad terminal band on the tail) anywhere in its non-native range, but are also treated as Naturalized Exotic in most places.

We encourage all eBirders to select “Red Junglefowl (Domestic Type)” everywhere except when birding the forests of South and Southeast Asia. And please, do not report pet chickens (even “free-range” birds that return to coops at night). Only report birds that have truly gone feral, but we know it can be hard to tell!

Additional Updates

The most important revision in North America is not a split but a lump Pacific-slope Flycatcher (Empidonax difficilis) and Cordilleran Flycatcher (Empidonax occidentalis) are being lumped–once again–as Western Flycatcher (Empidonax difficilis). These flycatchers were last considered a single species in 1989. The earlier decision to split is being reversed following new evidence of extensive interbreeding. The reclassification comes as a relief to many birders, given the previous difficulty of telling these two species apart in the field.

Also of note, 2023 continues the collaborative process of aligning global bird checklists, with the goal of a single consensus taxonomy going forward. It will take a few more years for eBird to fully incorporate these changes but we are committed to improving the clarity, efficiency, and accuracy of bird taxonomy through support for this team effort.