Grasslands make up a small part of New York’s landscape, but hold a number of species specific to the habitat—including several that are rare and of conservation concern. This guide is designed to help you find grassland birds while atlasing, providing crucial information for land management and conservation.

Quick Links

Planning your grassland atlasing

When you head out atlasing, it can be useful to have a plan, including which grasslands you want to target.

One of the quickest and easiest ways to find a grassland habitat near you is to use the Atlas Species Maps. Go to the Explore section of the NY BBA III and search for a common grassland bird, such as Savannah Sparrow or Bobolink. Locations with reports of these species indicate some kind of grassland potential: often a good spot to look for rarer species!

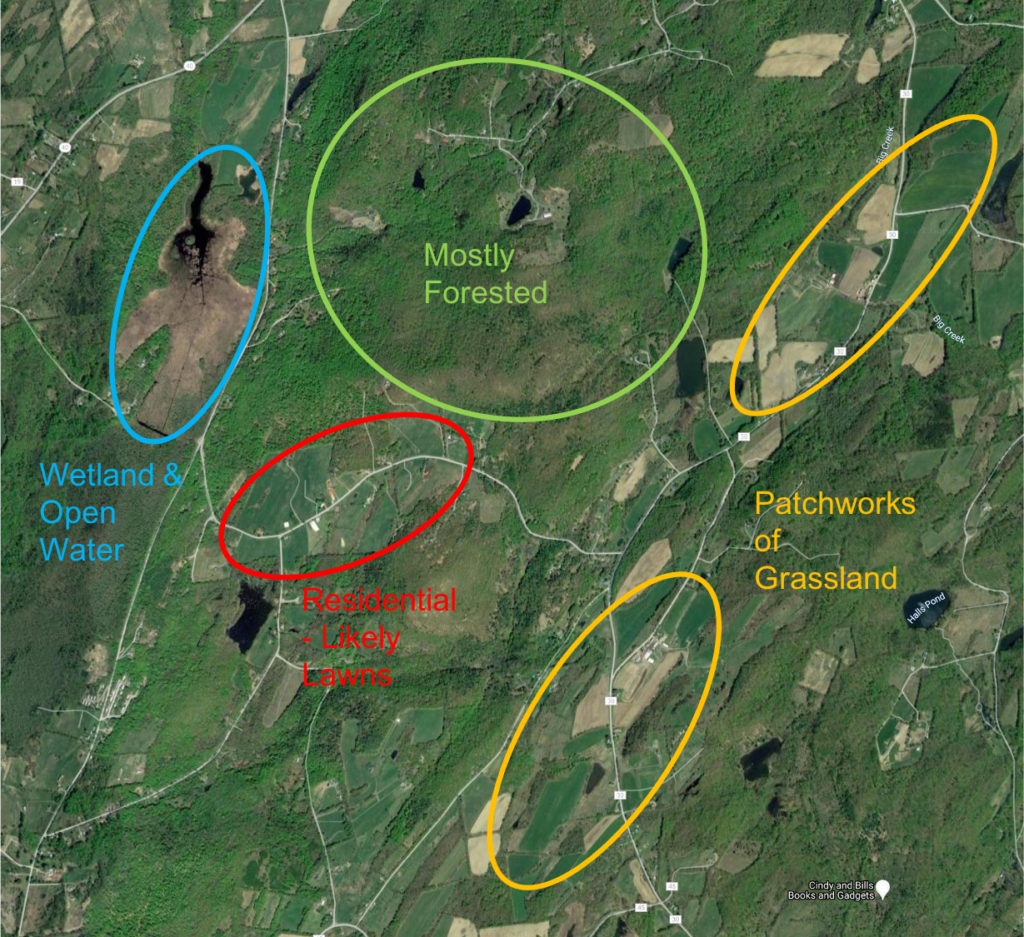

You can also look at a satellite image to find grasslands. Grassland habitats stand out as rectangular patches of solid green or tan, often together in a patchwork (see map). If you see a house in the middle of a green patch, it’s likely to be a lawn and probably doesn’t support many birds. Fields near roads are easiest to access (just bird from the road). If they’re farther from roads, use a landowner letter to request access.

Grassland habitats vary from grasslands and wild meadows to croplands, pasture, and old fields.

Recognizing grasslands on satellite images. Look for rectangular patches of solid green or tan, often together in a patchwork. Target grasslands near quiet roads for best atlasing conditions. Satellite image of the Hartford CE block, a priority block with no visits as of 5/4/21.

Finding grassland birds

Different types of grasslands hold different species—see below for species-by-species summaries of what to look for.

Grassland birds are often very vocal, and atlasing by ear is a great way to initially find species. This is good because they are often hidden out of sight in the vegetation when they aren’t busy singing or displaying. Many grassland species also sing at night, sometimes primarily at night. Detecting species at night can be a good way to know that a species is present, especially for species with songs that are harder to hear, like Grasshopper or Henslow’s Sparrow. If you detect a bird at night, it’s best to return during the day to try and observe other behaviors that indicate breeding.

Because the dense vegetation makes it hard for the birds to see each other, most species perform courtship with elaborate flight displays over the fields where they are not only easily observed by potential mates, but by onlookers as well. Other higher behaviors you are likely to observe include carrying nesting material, carrying food, feeding young, and recently fledged young.

We do not advise trying to find nests. Grassland birds and their habitats are sensitive and it is easy to trample their nests if you go traipsing through the field.

Species tips

The below tips cover the majority of grassland-focused species in New York, and focus on optimal habitats, the optimal time of year to search, and what sound(s) and behavior(s) to watch out for. There may be other habitats and behaviors that aren’t described, but the below descriptions are effective and efficient approaches for atlasing.

Species that are endangered, threatened, or special concern should be well documented and, optionally, submitted to the NY Natural Heritage Program.

- Upland Sandpiper

- Northern Harrier

- Barn Owl

- Short-eared Owl

- American Kestrel

- Horned Lark

- Sedge Wren

- Eastern Bluebird

- Grasshopper Sparrow

- Clay-colored Sparrow

- Field Sparrow

- Vesper Sparrow

- Savannah Sparrow

- Henslow’s Sparrow

- Bobolink

- Eastern Meadowlark

- Dickcissel

Upland Sandpiper (threatened)

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Large and extensive, open grasslands and meadows with a mix of contiguous short and tall vegetation to accommodate different phases of breeding (occurs in habitats like airports; fairgrounds; large intact conserved grasslands)

- Time of year

- Late April–early-August

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Upland Sandpipers have an unmistakable wolf-whistle song (coded as S), given perched or in flight. Keep an ear out for this song early in the morning—and you can even hear them sing at night! All other sounds should be coded as H. If you’re not hearing any “Uppies” singing or calling, scan along fence posts in April-May along the edge of large fields in case one is sitting up, and scour large fields for a small dove-like head poking out of the grass. See this species spotlight for more tips.

Northern Harrier (threatened)

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Large open fields, wet meadows, and marshes with dense vegetation to hide their nest.

- Time of year

- May–July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Look for their aerial display courtship display (C). The sky dance consists of males (and occasionally females) making a series of U-shaped undulations in flight ~20 m above the ground, ending with the bird landing at a potential nest site (see this video starting at 18 sec for a good example). They give a rapid series of kek or quik notes during these displays. Pairs (P) transfer food by dropping the food to each other in flight, known as a food drop. Later in the season, males will provide food for the incubating female and young (CF, FY, or FL). Harriers of both sexes strongly defend their nests from other birds, so you may see territorial fights (T) consisting of chasing, flight displays, and grappling talons.

Barn Owl

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Grasslands, marshes, agricultural fields, brushy fields, and other open habitats

- Time of year

- Year-round; active nests have been documented in November in NY!

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Barn Owls nest in abandoned buildings, barns, and nest boxes adjacent to open areas where they hunt for prey. They are nocturnal, so the best way to find them is by word-of-mouth (talk with local farmers), looking for lots of droppings and discarded prey items in open structures, and by listening for them at night. They make a variety of hisses and screams to make their presence known (S). Males perform several kinds of flight displays (C), including a “moth flight” where he hovers in front of a female for several seconds with his feet dangling. He also has a “nest showing display” where he flies in and out of potential nest sites while calling repeatedly (N). Females choose the final nest site, at which point they copulate and the male begins bringing food to her for a month before she lays eggs (C). Males continue to feed the brooding female and bring food to the nest for young (FY).

Short-eared Owl (endangered)

- Map of atlas records Note that this is a very rare breeder in NY and is sensitive to disturbance so we have worked with eBird to hide observations of this species. If you report observations of this species during the breeding season, the location will not be displayed publicly.

- Habitat

- Large, open grasslands and meadows with low vegetation

- Time of year

- Mid-April–mid-July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Short-eareds perform a dramatic aerial courtship display (C). Males display for females with an erratic flight with short dives (stoops) during which he claps his wings together under his body. All the while the male gives his hoo-hoo-hoo-hoo-hoo-hoo courtship song. In flight the pair may fly around together and grapple talons, but the display ends with the male landing on the ground near the female with his wings held high as he rocks side to side to impress her. Territorial disputes (T) involve flying directly at the intruder and grappling talons. This behavior will also be used against other predatory species, such as raptors and corvids, a sign of agitation (A). Males feed incubating females and young (CF, FY, or FL) and defend nests with distraction displays (DD). As with other owls, they will snap their bills and fan their wings out in a threat display (A); this is a sign that you are too close and need to back away immediately.

American Kestrel

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Open areas with a few scattered trees for perching, such as grasslands, forest edges, bogs, parks, and highway medians; they need a natural cavity (excavated by a woodpecker) or nest box for nesting

- Time of year

- April-July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Kestrels are easy to spot on their high perches overlooking fields (H). Their loud klee-klee-klee call is used for defending their territory (T) and as part of courtship displays (C). Females (sometimes males) fly slowly using stiff, fluttering wingbeats and with wings fully spread out and held just below horizontal. Males repeatedly fly up high, call, and dive, and sometimes transfers food to the female mid-flight. Males will escort potential mates to cavities within their territories (N) and the female will choose the nest site. Courtship feeding, with the male bringing food to the female, occurs for a month or more before and until just after egg laying (C). Males continue to bring food for the incubating female and later for the young (CF, FY). A long whine call is also given by courting individuals and when feeding young.

Horned Lark (special concern)

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Prefer short, sparse vegetation with patches of bare ground, such as fallow farm fields and grazed pastures.

- Time of year

- March–July, one of the earliest nesting songbirds in NY, often returning before the snow is fully gone

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Larks flutter over fallow fields in early spring before the snow even melts giving their tinkling songs (C). Watch for these courtship song flights around noon and at sunset. Courtship also occurs on the ground and is marked by the male drooping his wings and spreading his tail with his body in a horizontal position while he gives a chittering sound and struts around vibrating his wings and showing off his black chest for the female. Larks start singing their high-pitched tee-seep song (S) well before dawn and finish before sunrise, and then have a second bout of singing activity in the evening. Females respond to nest disturbance by scurrying and flying silently out of danger, but will perform a distraction display (DD) with wings spread accompanied by alarm calls if repeatedly disturbed. Young develop quickly but are fed by parents (FY) for a couple weeks after hatching. Since Larks have a short incubation and brooding period (<1 month), they can fit in multiple broods per year.

Sedge Wren (threatened)

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Sedge meadows with tall, densely packed sedges and grasses; also wet meadows, hayfields, and marshes

- Time of year

- A nomadic species with two distinct breeding periods that usually breeds in the Northeast during July-September

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- One of the least predictable nesting birds in NY, the Sedge Wren is nomadic and often inhabits different areas from year-to-year. They have adapted to their nomadic lifestyle by improvising their own unique song repertoire, with the result being high variation in song between individuals (compare this song vs this song, both recorded in NY). However the pattern of their song follows a consistent pattern. Their chip, chip, chrrrrr-rrr (S) is a dry series of trills that starts off with a few harsh introductory notes. Fortunately, Sedge Wrens do sing throughout the day and into the night (especially bright, moonlit nights) and occasionally pop out of the vegetation to sing from the top of the vegetation so you can usually get a visual confirmation. Given their secretive nature and living in dense vegetation, it is difficult to confirm breeding for this species, but you may be lucky and see one carrying some food (CF) or nesting material (N; note that they make dummy nests so you should use the code for wrens). Females also carry away fecal sacs (FS) on feeding trips.

Eastern Bluebird

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Open areas with a few scattered trees, such as meadows, agricultural fields, pastures, golf courses, and parks; they need a natural cavity (excavated by a woodpecker) or nest box for nesting

- Time of year

- April-August

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- With their bright blue back and rusty belly, Eastern Bluebirds are hard to miss. They often give away their nest site by sitting on top of a nest box (N), but if you wait a bit longer, you are likely to see them carrying nesting material (CN) or food (CF) into the box, or fecal sacs out of the box (FS). Males show off potential nesting locations for the female with a special nest demonstration display: male carries nesting material to a cavity, look around, enter the cavity, peak out of the cavity with the nesting material still in his bill, flies out and lands on top of the box or nearby, and waves his wings, all in an effort to demonstrate that it is a suitable nest location (N). Because cavities are in limited supply, there is a lot of competition from other cavity nesting species and both sexes will use a series of aggressive behaviors (wing-flicking, bill-snapping, and dive-bombing) to deter competitors and potential nest predators (A). Males reduce the frequency at which they give their loud, warbling song (S) once the female lays eggs. May have multiple broods.

Grasshopper Sparrow (special concern)

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Prefer dry grasslands and hayfields composed of nearly pure grass with some bare patches

- Time of year

- Mid-May–July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- The Grasshopper Sparrow is not named because it eats grasshoppers (though it occasionally does), but rather because their song sounds like a grasshopper. Their typical song (S) is rendered pee-trip-treee or tick tick pzzzzzz and is given from a perch. If you are lucky, you may be treated to their flight display (C) when they sing a series of squeaky, see-sawing notes. They will sing throughout the day, but less often in rainy or windy conditions. Males will chase rivals, sometimes combined with a wing flutter and song, which should be recorded as territorial behavior (T). They will perform a distraction display (DD) and feign injury if a predator approaches the nest or young. Also possible to observe adults carrying food for young (CF). May have multiple broods.

Clay-colored Sparrow

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Abandoned pastures and hayfields, regenerating clearcuts, and young conifer plantations (tree farms)

- Time of year

- May-July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Clay-coloreds are often overlooked but they sing their buzzy, insect-like song well into the heat of July. They sing from a low perch (not the top!) in a shrub at all times of day and occasionally at night (S). Territorial disputes are usually resolved with short chases or perch displacement (T). May defend their territory from Chipping and Song Sparrows (also T). Both parents feed (CF, FY) and care for young (FL). Adults defend their young and will feign injury to distract predators (DD).

Field Sparrow

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Old fields with some low shrubs, fencerows, forest edges and openings, powerline rights-of-ways, and young conifer plantations

- Time of year

- May-July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Listen for their distinctive song which sounds like a ping-pong ball bouncing on a table (S). Males give this song from the top of a shrub most often at dawn and early in the season, dropping off after the female starts incubating. Males defend territories through chases which may end in a tussle (T). Pairs often seen foraging close together before egg laying (P). Both parents feed (CF, FY) and care for young (FL). Adults defend their young and will feign injury to distract predators (DD).

Vesper Sparrow (special concern)

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Dry, open fields or pastures with short, sparse grass, scattered shrubs, and bare ground

- Time of year

- Mid-May–July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Vespers sing (S) most often in the early morning hours, but also throughout the day with a second burst after sunset, which is where they get their name. Look for them giving their musical listen to my evening sing-ing-ing-ing song from an elevated perch. Males court females (C) by running after them with their wings raised and tail spread and periodically jumping into the air in song. Both adults defend nest and young with a distraction display (DD) that includes feigning injury. Both parents feed (CF, FY) and care for young (FL) and remove fecal sacs from the nest (FS). Can have multiple broods.

Savannah Sparrow

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Large, open hayfields, pastures, meadows, and grasslands with few trees

- Time of year

- Mid-May–July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Savannahs have a three-part, buzzy, insect-like song (S) that can be rendered as zit-zit-zit-zeeee-zaaay. Look for males singing from elevated perches throughout the day and into the night. Territorial disputes (T) consist of chasing, intimidation by holding wings vertically, and making short fluttering flights with legs dangling. Flutter-flights can also be used against other species (humans and cowbirds) as a sign of agitation (A), and are used by males to court females, so context is key if you observe this behavior. Females give a distraction display (DD) if the nest is approached and adults may mob potential predators (A). The best ways to confirm breeding are to look for carrying of nesting material (CN), food (CF), eggshells, or fecal sacs (FS). May have up to two broods.

Henslow’s Sparrow (threatened)

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Fallow, weedy, often moist fields and meadows with tall, dense vegetation and a thick layer of litter (i.e., a field that hasn’t been mowed for at least 1-2 years)

- Time of year

- May–July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Henslow’s Sparrows are cryptic, unpredictable, and rare breeders in NY. They occupy different fields from one year to the next and they have a nondescript song that is often easier to hear in the nighttime (best is on clear, moonlit nights) when there is less background noise. Males give their non-musical tsip-a-lik song (S) from high perches in the grass or from a shrub, most frequently at dawn, dusk, around midnight, and during rainy weather. They spend much of the rest of their time foraging near the ground well out of sight. While not much is known about their breeding biology, you may (if you are extremely lucky) see them chasing intruding males (T), hear them giving a distinctive, high-pitched alarm call when raptors are nearby (A), or see them carrying of nesting material (CN), food (CF), eggshells, or fecal sacs (FS). Given the rarity and sensitivity of this species, we again remind you not to trample the fields in search of nests or to get a better photo or recording.

Bobolink

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Large, open hayfields and meadows with grasses and legumes

- Time of year

- May–July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- As one of the most common grassland birds in NY, the aerial displays of male Bobolinks are a frequent sight in May and June over most patches of grassland. They give their R2D2-like, bubbly song from exposed perches (S) and as they flutter over the field in an attempt to attract mates (C). When a new female lands in a male’s territory, he performs a ritualized courtship sequence (C) where he repeatedly hovers over her, circles overhead, sings briefly, and then drops to the ground while dangling his legs and holding his wings upward. Males spend most of their time attracting mates or engaging in territorial chases and fights (T) until the young hatch. Females are scarce during incubation, and then both adults can be seen busily providing food for young (CF, FY, FL).

Eastern Meadowlark

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Large grassy meadows, pastures, hayfields, and some croplands

- Time of year

- Late April–July

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- Their song (S) is a series of clear, flute-like whistles that sound like eas-tern mead-ow-lark or spring-of-the-year, usually given from an exposed perch, but also occasionally from the ground or in flight. Singing is most frequent at dawn with another bout in late afternoon. Courtship displays (C) involve aerial chases and duetting, interspersed with posturing on the ground that show off the male’s yellow breast and black crescent. Once pairs are established, they spend a lot of time near each other and can be observed foraging and looking for nests together (P). As with other grassland species, the best chances to confirm breeding are observing carrying of nesting material (CN), carrying food and feeding young (CF), and observing fledglings (FL).

Dickcissel

- Map of atlas records

- Habitat

- Grasslands, croplands, hayfields, and lightly grazed pastures with tall, dense patches for nesting

- Time of year

- June–July; irruptive, so they may be present one year and absent the next

- Key tips, sounds, and behaviors

- An uncommon species in NY, Dickcissels are easily recognized by their bright markings (reminiscent of meadowlarks) and their eponymous dick dick dick-cissel or dick-dick-see-see-see song (S), which can be heard almost continuously throughout the day and is delivered from conspicuous perches. Males often have multiple mates, so they spend the majority of the breeding season defending their territory from other males. They patrol the boundaries of their territory and will approach neighbors on the ground with a sidelong glance. Intruders are chased in flight often followed by intense fighting on the ground (T). Again, the best chances to confirm breeding are observing carrying of nesting material (CN), carrying food and feeding young (CF), and observing fledglings (FL).

Conserving Grassland Birds

Over the last 60 years, grassland breeding birds have declined throughout North America. Breeding Bird Survey data show that over 90% of grassland bird species in New England have shown negative population trend estimates, while none show positive trend estimates. The 3 Billion Birds Lost report noted a 53% population loss in grassland birds since 1970, more than any other species group. Between the first two New York State Breeding Bird Atlases, the statewide distribution of grassland breeding birds declined, with the distribution of five species declining by over 50 percent. Clearly, grassland birds need our help, and your atlasing helps map grassland birds across the state. Thank you!

Best Management Practices for Grassland Birds

Best Management Practices for Grassland Birds