Horned Larks are among the earliest songbirds to breed in NY. They often settle down in sparse agricultural fields before the snow is gone. Their tinkling song and dramatic courtship displays are harbingers of spring. While it can be difficult to spot these well-camouflaged birds during the breeding season, you can improve your odds with a few tricks up your sleeve.

Top tricks

- Look early. Keep an eye out for breeding behaviors starting in March. Larks are one of the earliest breeding songbirds in the state.

- Target the right habitats. Check large, low-lying open areas with little to no vegetation, such as agricultural fields, old meadows, airfields, and even coastal sand dunes.

- Keep scanning. Larks often place their nest next to a small tuft of grass or a rock and if they are past the courtship stage, you won’t see them until they move.

- Use a scope. They actively avoid areas with trees nearby, so you may need a scope to scan fields from the nearest roadside.

- Listen for courtship flights. Learn the flight song that males give during courtship. The song is often described as a series of tinkling notes that they give while flying high up in the air and then diving towards the ground at a high speed, only pulling up just short of the ground.

- Don’t be deceived. Larks like to land and take off at quite a distance from their nest. If you see one landing, follow it until you spot the nest or a young bird.

Continue reading to learn more about Horned Lark breeding habitat, phenology, identification, breeding behaviors, and conservation.

Where to find them

Horned Larks are denizens of open, bare lands year-round. We are most familiar with them in the winter when they move around in large flocks on roadsides, but they are more difficult to see during their breeding season without the snow that contrasts with their brown bodies.

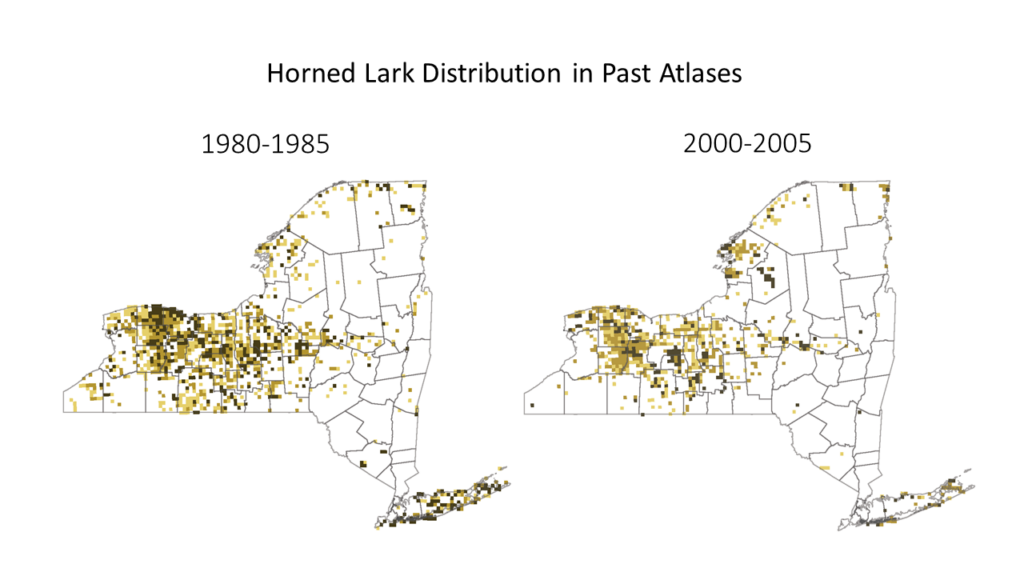

The largest concentrations of Horned Larks in NY are in the lowland regions of the Great Lakes Plain, central Appalachian Plateau, Mohawk Valley, and Coastal Lowlands (see maps below). Within those regions, they prefer to breed in areas with no or very short vegetation. In New York, they are most common in agricultural areas, particularly fields with stubble from the previous year’s crop, such as is found in central and western NY. On Long Island, they also nest on sand dunes with beach grass. See where they have been observed in this Atlas.

Distribution of Horned Lark during the first and second Breeding Bird Atlases.

Larks avoid areas with tree cover and need large open areas to be successful. The Pennsylvania Breeding Bird Atlas (conducted from 2004-2009) found that Horned Larks did not nest in blocks with less than 300 acres (120 ha) of arable land but were found in almost all blocks with at least 2000 acres (800 ha) of arable land (for context, one square mile is 640 acres).

Nests are often located next to a tuft of grass or a small mound (see photo below). If you come across a likely area for larks and they are in the incubation stage, keep watching for several minutes because they may not be visible until they move out from behind a furrow, hillock, or other tuft of vegetation.

When to find them

Nesting begins in March when there may still be snow on the ground. The female selects a nest site, and over the course of one or two days, she digs a shallow depression in the ground with her bill. She weaves a nest out of fine grass or roots and lines it with plant down, rootlets, and feathers. “Pavings”, such as dirt clods, dung, or small pebbles, are regularly placed at the nest entrance. After 2–4 days, her construction efforts are complete and she begins laying 2–5 speckled-brown eggs. On early nests, she might begin incubation with the second-last egg, but normally she will wait for her clutch to be complete. Incubation lasts eleven days; in cold weather, an additional day may be required. The newly hatched nestlings look like downy moss, until they open their mouths and reveal a distinctive, attention-grabbing orange and black pattern (see photo below).

The nestlings will stay in the nest for ten days. The female does all of the brooding, but both parents help provision the chicks. A parent may return with food as often as once every five or six minutes. Adults eat primarily seeds all year long, but nestlings are provided with a diet composed mostly of beetles, grasshoppers, and caterpillars. Adults are stealthy when approaching the nest, and land 60 or 70 feet away. Likewise, when they leave the nest they walk 15 or 20 feet before flying away, often carrying a fecal sac. After ten days, the chicks will leave the nest but remain in close vicinity, crouched and motionless. Unlike adults, young Horned Larks do not walk, but rather hop. A week later, they are capable of weak, fluttery flights, and can finally walk and fly well at 27 days. At this point, they are independent of their parents and will form roaming flocks with other juveniles.

Assuming the habitat is still suitable, the adults will begin a second brood. Horned Larks are intolerant of any vegetation growth though, and if they deem it too long or dense, they move to a more suitable location—even if a nest is already underway.

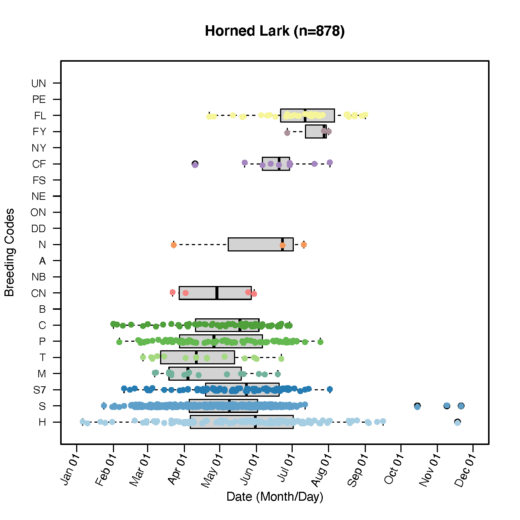

Breeding phenology plot showing the time of year each breeding behavior was recorded for Horned Lark based on Atlas data from 2020-2021 (878 observations). Standard box plots with median and first and third quartiles plotted. Based on raw, unvetted data.

Breeding calendar

These are the general time periods when you will see each stage of breeding, but note that individuals may nest earlier or later as they are often double-brooded. They have been known to nest at the end of February and fledglings may be seen as early as mid-April!

Mid-March–mid-May: arrival, pair formation, and courtship

April–June: nest building, egg laying, and incubation

June–August: brooding, parental care, fledglings

September–mid-March: loafing, learning, overwintering

Identification

With a good look, adults are nearly unmistakable. Sexes can be separated by the males’ slightly larger size and darker, bolder colors on the face and chest. Juveniles are more nondescript, and could perhaps be taken for a sparrow, like a Vesper Sparrow. Vesper Sparrows will even occupy similar habitat, but they prefer more shrubby growth. Juvenile Horned Larks have a mottled appearance on their upperparts, a black tail, and lack the white eye ring, rufous wing patch, or streaked back that Vesper Sparrows have. Regardless of any morphological similarities, habitat and behavior remain strong clues for correctly identifying Horned Larks.

Cool fact: Horned Larks are holarctic, meaning they occur across North America and Eurasia. As a ground nester, this means they must blend in with a wide variety of soil colors to avoid predation. They have adapted by varying the color of their back feathers to match local soil color. Birds in the more arid western states have paler backs than those that live here in the cooler, wetter east and to our north.

Behaviors to look for

Horned Larks are exceptionally early nesters and begin forming territories and monogamous pairs in February. However, New York is also an overwintering destination for more northern populations of Horned Larks. Until mid-April, be aware that not all larks you see are breeding, so don’t waste too much time on a big migratory flock.

Singing. Breeding males select a territory and declare their ownership with a “ground” song. This song is given from a slightly elevated position, such as a rock or a dirt clod, but rarely from a truly elevated perch like a shrub or a fence post. Any intruding males will be chased from the territory; these chases may result in physical altercations. Larks start singing very early in the morning, well before dawn, and have a long, complex dawn song.

Courtship. Their aerial song synchronizes function with beauty. Rather than being used in territorial defense, it is used in courtship. Males fly as high as 800 ft to perform this display, with long glides corresponding to a light tinkling song that recalls delicate, ethereal bells. Their song begins slow and haltingly, accelerating towards the end.

Nesting. Nests are difficult to find, but this is largely unnecessary and can be very disruptive. The open habitat Horned Larks prefer provides ample opportunity to confirm them at a distance from April to August. However, if you see adults returning to the same location repeated, you can use code N for a probable nest site.

Carrying food and nesting material. The most commonly used code for larks so far in the Atlas is CF for carrying food. The adults stuff their bills with caterpillars and other insects to feed the young. While less commonly observed, it is possible to see them carrying small twigs and grass to line their nest (CN).

Removing eggs or fecal sacs. Larks remove fecal sacs and eggshell fragments from the nest, so it is possible (though uncommon) to use the FS code.

Fledglings. Use the FL code for recently fledged young. Fledglings have a yellow gape, short tail, downy feathers, begging, and clumsiness. Young Horned Larks molt out of their juvenile plumage in August and flock with other juveniles, so beware flocks of young birds in midsummer. These are not recently fledged and do not represent local breeding, and should not receive a breeding code. Instead, look for fledglings that hop rather than walk, that have pinkish legs and yellowish bills rather than grayish legs and bills, and for interactions with nearby adult Horned Larks.

Conservation and Management

Grassland birds are the most rapidly declining group of birds in North America. Unlike other grassland birds, larks are early nesters and can often get a nest in and fledge young before the fields are planted in the spring.

Horned Larks colonized the Northeast in the mid- to late-1800s, with the first known nest found near Buffalo in 1875. This eastward range expansion was a result of increased farming and the creation of more open space. Since the mid-1900s their range has been retracting as farms are abandoned and grow back into forest. In addition to these landscape changes, farmers have changed their crops from hay to corn and alfalfa, which seems to have further reduced their breeding population in NY. And with a warming climate, fields are sown and harvested earlier in the season. All this adds up to less suitable habitat and a shorter time period in which to successfully nest.

Horned Larks are a species of concern in NY. Data from the third Atlas will be invaluable in documenting their current status.