Long-eared Owls are a cryptic and enigmatic species found across North America, Europe, and Asia. While they have a range that spans the northern hemisphere, Long-eared Owls are often difficult to find locally due to their preferred habitat of thick conifer forest, effective camouflage, and infrequent hooting behavior. Long-eared Owls are also not often seen hunting outside of nocturnal hours, where they search for small mammals like voles in open grassland and shrubby fields next to dense forest cover.

Top Tips

- Plan to be out at sunset and into the night in late June through August to listen for the more vocal fledgling young and their begging calls. While adults aren’t heard as regularly, or effectively, fledglings and juveniles will regularly and sometimes loudly beg for food like many other owl species.

- Watch for silhouettes perched or in flight on clearer and moonlit evenings at the edges of densely forested areas where they meet up with open fields. Long-eared owls will often perch at the edge of dense forest while hunting, and even on fence posts and other more open objects once they have cover of darkness.

- Earlier in the season (March-May) males are more likely to frequently call, and can be spotted making courtship flights in a zig-zag pattern over desirable habitat. Males will also perform wing clapping as part of courtship flights, though you will need to be fairly close to hear it.

- Try going into a dense conifer stand where the canopy has heavy overlap during the day. While walking through, keep an eye out in some of the thickest patches for stick nests that Long-eared Owls might be using. Depending where they are in their nesting cycle, they may even try to defend their nest with hoots and calls. Incubating females tend to sit very tight on the nest and remain silent.

Where to Find Them

While Long-eared Owl nesting habitat can vary as to the specifics of tree and plant species in an area, they appear to prefer dense conifer stands that are next to open fields. Long-eared Owls seem to prefer spruces, tamarack, and cedar for their dense nesting and roosting areas, while the adjacent open fields may be pastures, grasslands, meadows, or even shrubland. Although less common, Long-eared Owls will inhabit mixed deciduous stands that are as characteristically dense as conifer stands, so don’t rule out a spot simply because there are few broad-leaved trees in the mix. If you see a thick stand of trees next to a nice open grassland, it may be worth watching and listening in the area at sunset and into night.

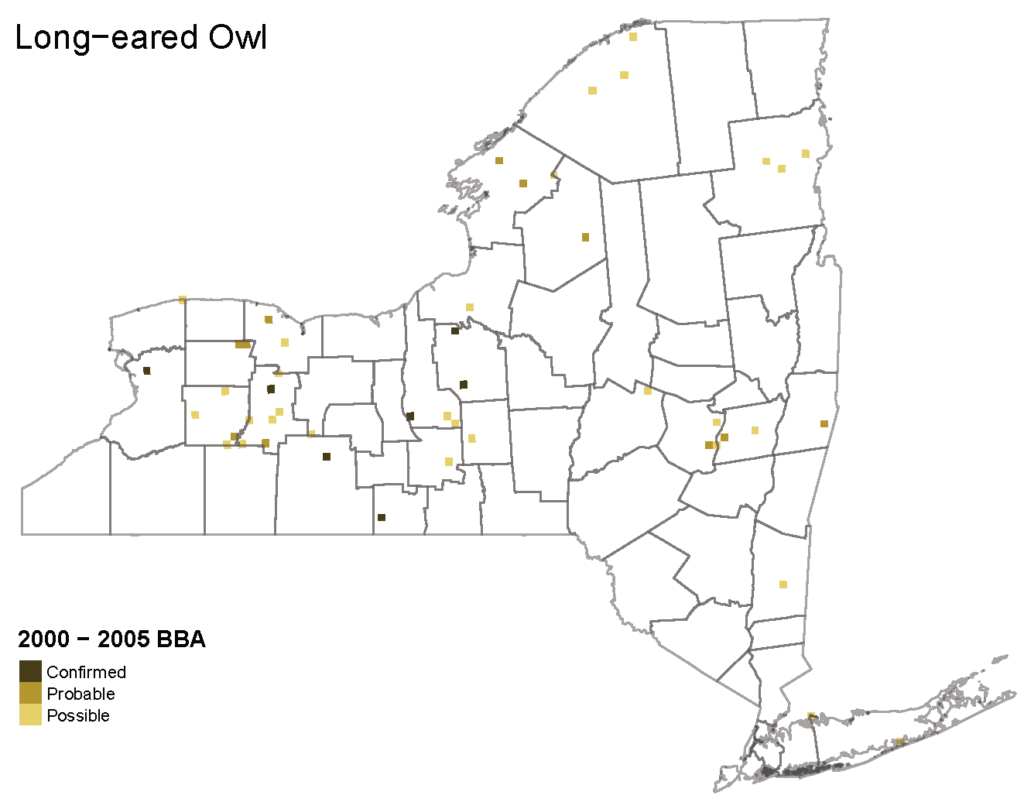

Where Long-eared Owls breed in New York is particularly difficult to generalize due to a low number of historical documentation, seemingly usable habitat across the state, and the Long-eared Owl’s likelihood to change nesting sites every year. Long-eared owls are also difficult to generalize as the “dense coniferous forest” aspect of their breeding habitat is not necessarily a specific species of conifer, and can include deciduous trees in the mix as well. If you were a Long-eared Owl, the perfect patch of dense coniferous forest next to a field would also need to have an old nest built by another species for you to breed there. Nests are historically documented throughout most of the state’s major regions with the exception of much of the southern tier.

See the current Atlas map. Be the first to document them!

Distribution of Long-eared Owl from the 2000-2005 Atlas.

When to Find Them

Long-eared Owls can be found in New York year-round, but are more easily detected during the winter months when individuals communally roost in dense coniferous forest patches. These winter roosts make them easier to find, but are not likely to indicate breeding behavior. Starting in March, and possibly early February, Males will begin their aerial courtship flights and more frequent hooting while attracting females and defending their territory.

Long-eared Owls are most vocal when the young have left the nest and regularly beg for food. This time period can begin in June and extend as late as September. July and August are likely the best two months to listen for the shrieking begging calls of fledglings. As the season progresses to late August and September, begging will decrease as the fledglings become self-sufficient.

Even though there are times of year when you are more likely to detect Long-eared Owls, it is always possible to get lucky and hear hoots outside of their peak calling period. If you are doing nocturnal atlasing near Long-eared Owl habitat it is always worth listening closely and watching throughout the breeding season.

Breeding Calendar

- March to May: Arrival, pair formation, courtship, and nest selection

- May to June: Nest building, egg laying, incubation, nestlings, feeding young in nest

- Jun-September: Feeding fledglings

- Sep-Oct: Departure

How To Find Them

Finding the right landscape is often the first step to having success in finding breeding Long-eared Owls. While their preferences can vary as to the specifics of tree and plant species in an area, they are clearly related to dense conifer stands that are next to open fields. Long-eared Owls seem to prefer spruces, tamarack, and occasionally cedar for their dense nesting and roosting areas, while open fields may be pastures, grasslands, meadows, or even shrub land. While less common, Long-eared Owls will inhabit mixed deciduous stands that are as characteristically dense as conifer stands, so don’t rule out a spot simply because there are few conifers in the mix. If you see a thick stand of trees next to a nice open grassland, it may be worth watching and listening in the area at sunset and into night.

One method that is considered effective for finding breeding Long-eared Owls is to listen for the squeaking of fledglings begging for food. Unlike waiting and listening for adults to hoot unreliably, the fledglings are likely to audibly beg for food regularly throughout parts of the evening, particularly right after dusk. This method requires waiting until later in the season for juveniles to be out of the nest and somewhat mobile in the forest. This time-frame will typically span from June until August depending on when the first eggs are laid. Finding Long-eared Owls by this method has the added benefit of confirming fledged young in that area.

Like most nocturnal birding, listening for the various calls of Long-eared Owls is commonly how they are located. However, nests can be found by strategically walking and looking in dense coniferous forest. Long-eared Owls appear to prefer taking over old nests that are in places where canopy is thick, especially with overlap between multiple trees. Keep an eye out for places that look particularly dense in the canopy, especially if you see signs of an old stick nest. Early in the nesting stage, female Long-eared Owls sit tight on the nest when intruders are present. It is important to keep disturbance to a minimum if you do find a nest, particularly if the adults defend the territory. Document your observation and leave the area as quickly as possible.

Silhouetting is another method to consider doing adventitiously in the correct conditions, and is best practiced on nights where the moon is producing enough light to help see the outlines of Long-eared Owls while they are perched on an edge, in the open, or in flight. This method can be used as birds return to choose their nesting areas (as early as March), while they hunt, or when the males make courtship display flights. Long-eared Owls can be extremely secretive and difficult to see even when fledglings are heard begging nearby, so don’t be discouraged about a promising area before there is a chance to listen for begging juveniles, or catching the adults hooting.

Behaviors To Look For

While difficult to locate, Long-eared Owls do display behaviors that can be signs of breeding. Their nocturnal habits make viewing behaviors difficult, though not impossible, on evenings with clear skies and bright moonlight.

- Singing. Long-eared Owls are often only found by a hoot, or several if you are lucky, and the code S (singing) can be used.

- Pair in suitable habitat. Code P (pair) should only be used if you can clearly identify that you are observing a male and female in suitable habitat.

- Courtship, Display, or Copulation. If you are lucky enough to see a male Long-eared Owl flying in their zig-zag pattern over suitable habitat and making wing claps, you should use the code C.

- Occupied Nest. Occupied nest (ON) can be a useful code for Long-eared Owls as seeing eggs or chicks in the nest may be impossible. You can use this code when there is clearly a female incubating or brooding on a nest, but the contents aren’t visible.

- Recently fledged. Recently fledged Long-eared Owls seen or clearly heard begging, but not seen being fed by parents (in the rare case of which case you would use the feeding young FY code) can gain the code FL.

Life History

Long-eared owls are characterized by their long ear tufts that can help easily separate them from their relative the Short-eared Owl. They are renowned for their seemingly secretive behavior and ability to blend into their forest habitat.

Long-eared Owls rely heavily on small mammals for food, though they will occasionally take birds when possible. It is common to see them swallow mammalian prey whole, though they appear to be a bit more particular about eating birds when they do catch one. Mammal prey items are usually small, between 10-100 grams, and are often species of voles, deer mice, house mice, shrews, and juvenile rabbits.

They prefer to hunt over open fields, but will hunt in open forest below the canopy. They can catch mice by hearing alone in complete darkness, and like most owls, Long-eared Owls have wings and feathers adapted to silent flight.

Long-eared Owls do not build their own nests, but instead use stick nests built by other species in prior seasons. Their nests of choice include those built by American Crow, Common Raven, Cooper’s Hawk, occasionally Buteo nests, and they will even use artificial nest baskets where other suitable nests are not available. They tend to prefer finding nests in dense clumps of trees for cover over being exposed in single trees or tree rows.

Females will typically lay 4-5 eggs (but can lay as many as 10!) that only they will incubate. Eggs will hatch after 26-28 days. While the female is incubating, the male will bring her food at the nest, and close to hatching he will sometimes stockpile some food in the nest for feeding young.

Parents will feed and defend fledglings until they are between 6.5 to 11 weeks old. Interestingly, the females will typically stop feeding and caring for their young up to 3 weeks earlier than males. In some cases, males will even care for their young until they begin to migrate if they had a late start in breeding that season.

Although Long-eared Owls lay 4-5 eggs, they have somewhat low success in rearing young to independence. Their eggs and nestlings can be prey to mammals and raptors. Raccoons and even porcupines will eat eggs if discovered, but there are few records confirming nest predators. Nestlings and fledglings can become prey for other birds of prey, and crows and ravens can key in on nests disturbed by human interaction. Therefore, be cautious if you find a nest and cause as little disturbance as possible!

As a migratory species, Long-eared Owls typically begin moving to their wintering grounds in October, although their migratory patterns are largely unknown. In some cases, they may make short distance migrations, or small local movements rather than a long distance migration, especially if food is locally available. Once they have landed in their chosen wintering area, Long-eared Owls sometimes have communal roosting areas that can have 2-20 individuals, but there have been roosts of up to 100 recorded! These winter roosting areas are often where birders get their best and most reliable looks at a Long-eared Owl when they are found, however there is no known record of these communal roosts having a relation to breeding or breeding behavior.