By Julie Hart & Matthew Young. About the authors

Crossbill. Bec-croisé. Kreuzschnabel. Pico cruzado. In every language, the most distinctive character of a crossbill is its amazing bill. The tips of the mandibles (the upper and lower parts of the bill) cross in opposite directions. This unique adaptation makes crossbills super efficient at extracting seeds from conifers. If you’ve ever tried to take apart a dried pine cone, you know how difficult it can be. But crossbills have mastered this art. They shove the tip of their bill in between the cone scales, brace themselves with their feet, then use the strong leverage of their crossed bills to pry open the scale and pull the seed out with their tongue. Watch a video of this amazing adaptation below.

This unique adaptation has allowed crossbills to take advantage of this untapped resource, but it also makes them highly dependent on conifer trees, so much so that they have adopted a nomadic lifestyle flying long distances to track large cone crops. This adds to their appeal for us birders, because we don’t know when or where we may run into them. But we can increase our chances by following large-scale movements of crossbills (called irruptions) and learning a bit about their biology.

How to Find Them

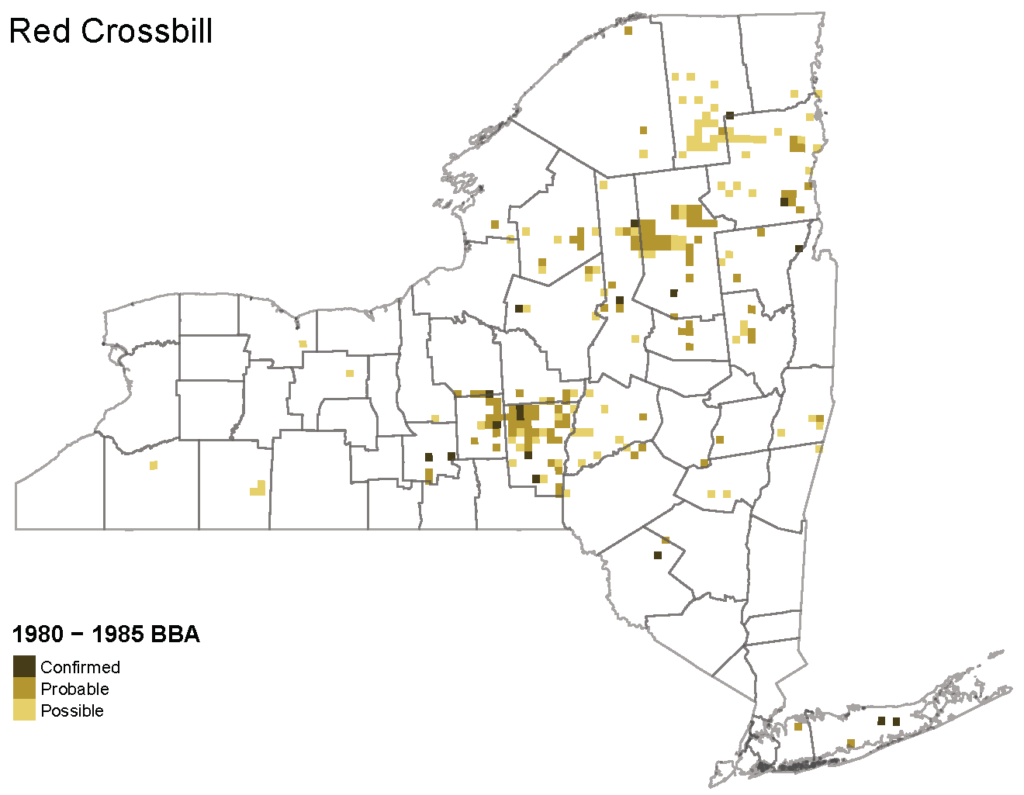

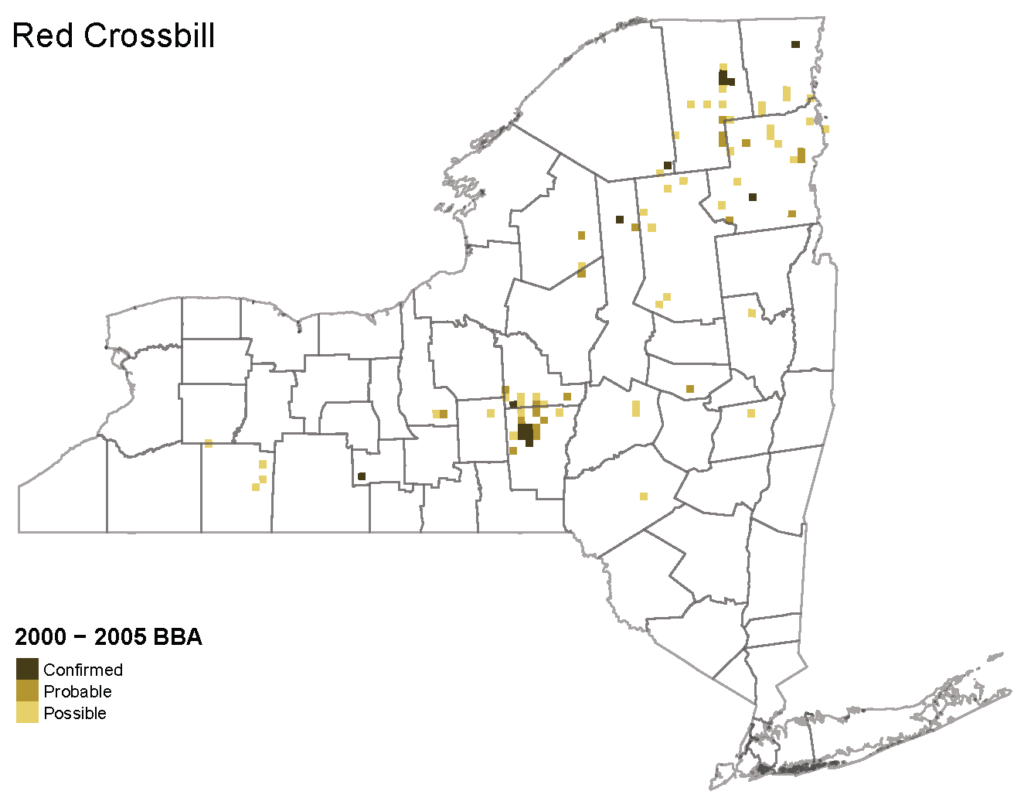

Crossbills are dependent on conifers for food. In irruption years, look for stands of conifers with a lot of cones (i.e., a large cone crop). The preferred conifers in our region are pines, spruces, and hemlock. The most reliable areas of the state are the Adirondacks and central NY, but they are probably under-surveyed in the Taconics and Allegany region. See the map of sightings in eBird for NY, the current Atlas, and the maps from the previous two atlases (below).

Listen for their distinctive “kip kip kip” flight (or contact) calls to cue you in to their presence. Crossbills tend to be pretty noisy when they are around since they are usually in small groups and frequently give this call.

Crossbills, like a number of other boreal specialists, are fairly tame. They spend most of their time up in the canopy eating seeds, so they often don’t change their movements when people are nearby. They are more skittish when they are gritting, that is, eating small stones and salt from roadways (see photo).

Find additional practical tips on how to search for crossbills in this great article by Ryan Mendelbaum on the Finch Research Network.

Identification

There are two species of crossbills in NY, Red Crossbill and White-winged Crossbill. You can tell Red and White-winged Crossbills apart by the (lack of a) wing patch. White-winged Crossbills have a bright white wing patch while Red Crossbills don’t.

Adult males are a deep brick red, whereas females have olive-green to yellowish bodies with a pale gray or whitish throat. Immature males can look like adult males, females, or somewhere in between.

Juveniles are streaked brown and can be easily misidentified as juvenile House Finches because the crossed mandibles are not fully developed, but you should see or hear an adult in the vicinity to help you make the correct identification. It takes 30 days from hatching for the bill to be fully crossed and birds fledge at 15-25 days.

There is a lot of variation within Red Crossbills, a species that ranges across North America, Europe, Asia, and northern Africa. There are 10 recognized call types in North America (one type is now recognized as a separate species, Cassia Crossbill, formerly type 9) that have slightly different bill sizes and each specializes on a different suite of conifer species. Types are told apart by their call notes, hence they are called call types. In NY, we mostly have call types 1 and 10, but also some type 2s and 3s. Type 1s are most common south of the Thruway (I-90) and type 10s are most common north of the Thruway. Learn more about the different call types.

Extra credit – Help track call types

The most important thing for the Atlas is to document the presence of crossbills breeding in the state. That said, you can take a simple step to provide additional information to increase our understanding of the distribution of the different call types in NY. The call types are distinct enough that, in most cases, a short sound recording will allow us to identify the birds to type.

Whenever possible, make a recording of any crossbills you encounter. Here’s how:

- Make a recording on your smartphone in .WAV format

- Upload the recording to your eBird checklist as “Red Crossbill” (with no type designation)

- Send a copy of your checklist to the Finch Research Network for identification (info@finchnetwork.org)

- If an expert can identify your recording type, change your eBird entry

More details on how to record and submit records of crossbills.

Breeding Calendar

Red Crossbills are nomadic, with the call types that occur in the Northeast tracking cone crops across the boreal forest of Canada and sometimes irrupting further south in the Appalachians, Rockies, and Sierras. They often travel large distances between breeding attempts. However, they always time their breeding to match the cone cycle.

Crossbills are opportunistic, taking advantage of cone crops when they are available, which means they can breed multiple times a year or not at all. In the Northeast, they exhibit two distinct breeding periods, once in the winter (Jan-April) and again in the summer (Jul-Sep). If you’ve ever tried to pull apart a pine cone, you know they can be tough. That’s why crossbills breed in the winter when the cones from the previous year have weathered and are easier to break apart, or in the summer, when the cones are fresh and soft.

Since we don’t have many breeding records for crossbills in the Atlas (yet!), we can’t provide a detailed phenology chart. Instead, here is some information on the different nesting stages to help you gauge the timing of different behaviors (next section), whether you find them in their winter or summer breeding period.

Incubation. The female incubates her three eggs for 14 days. Females are fed by the males during winter nesting so that the eggs are not left exposed to the cold temperatures.

Nestlings. The female stays on the nest almost constantly for 5 days after the young hatch. After that she takes longer forays away from the nest to forage. Both parents feed the young. Fecal sacs are consumed for the first few days, after that they are deposited on the rim of the nest.

Fledgling. Young fledge at 15-25 days, depending on food availability and outside temperatures. They may return to the nest for the first few days after fledging to roost. They may stay near the nest for up to a week being fed by the parents. After that, they follow the parents around closely. Parents feed young for a month or more after fledging, until the bill of the young is fully crossed and they are able to forage efficiently on their own.

Behaviors to Look For

Crossbills spend a lot of time high up in the tops of trees, so they can be hard to confirm breeding. It can also be difficult to tell a roaming group from a breeding group because they sing even when they are not actively breeding. In general, breeding groups are small, in an area with a large cone crop, and the males sing a repetitious song from a consistent song perch. Here are the most common behaviors you will encounter and how to code them.

Singing. Birds sing (S, S7, M7) in flight or perched from the top of a tree. Songs, described as pit-pit, tor-r-ree, tor-r-ree, are variable and often contain a mix of call notes, trills, and whistles (example 1, example 2). Both sexes sing, but males are louder and sing more frequently.

Pairs. A male and a female crossbill flying together doesn’t always indicate a mated pair since they move around in small groups year-round. Breeding pairs (P) can be recognized by a male and female flying together from a nest site to a salt lick or communal drinking site.

Threat displays. Crossbills nest in small groups and forage as a group, so they aren’t territorial in the traditional sense. However, they do compete over food and perches, so you may see them getting aggressive towards other birds, sometimes even ending in chases and physical fights. There is still much to learn about breeding behavior, with territoriality around the nest one of the unknowns, so use extra caution with the T code and only use it in the rare cases where you see two breeding males fighting over a mate, song perch, or nest. Another aspect of crossbill behavior we are still learning about is the context for toop or alarm calls. It seems that crossbills give toop calls in a variety of situations when a perceived threat is nearby. These calls are more emphatic and harsher than normal contact notes. Depending on if toop calls are given in response to another crossbill or a predator, use the T or A code.

Courtship. Males court (C) females with chasing, courtship feeding, and billing (touching or grabbing the bills of potential mates). Their courtship flight display (C) consists of birds singing in flight with slow, exaggerated wing beats.

Nest building. Both sexes supply twigs, grasses, lichens, and other materials for the nest (CN), but the female does most of the building (NB). Their cup nests are well concealed in conifer trees 2-20 m off the ground.

Feeding young. Parents feed young (FY) by regurgitating whole seed kernels and fluids from their crop. You are unlikely to see this at the nest, but you may see this behavior with fledglings.

Fledgling calls. Juveniles make chitoo calls up until they are independent, about 60 days after hatching, and can be coded as FL for recently fledged.

Annual Finch Forecast

Each year a finch forecast is compiled that predicts the movements of finches across North America based on cone crops in the boreal forest. The 2022 Finch Forecast will come out on Sept 22 and will be posted on the Finch Research Network website.

Learn More

- All About Birds

- Audubon Bird Guide

- Xeno-Canto

- eBird Species Page

- Crossbills of North America (eBird blog post)

- Keeping track of these boreal nomads is notoriously difficult (Audubon blog)

About the Authors

Julie Hart is the Breeding Bird Atlas project coordinator. She studied the impacts of climate change on Cassia Crossbill for her Master’s research. She has captured and measured the bill size of hundreds of Cassia Crossbills and is familiar with type 2, 5, and 9 (Cassia) crossbills. She is continually frustrated about her unfamiliarity with the call types of the Northeast.

Matt Young is President and Founder of the Finch Research Network. He has been studying crossbills for 25 years. Matt has lived in NY for 25+ years, so if you submit a crossbill recording to be identified to call type, he is most likely the one who will assess your recording.