Did you know there are over 2,000 volunteer eBird reviewers around the world? Volunteer reviewers play an important role ensuring the eBird database remains reliable and accurate for science and conservation (learn more about the eBird review process). eBird is incredibly grateful to our volunteer reviewers for their dedication to eBird’s data quality.

The eBird Reviewer Spotlight helps you get to know eBird’s volunteer reviewers a little better. These articles are written in the reviewer’s own words and reflect their experiences as reviewers, eBirders, and members of the birding community. In this spotlight, Michael Schrimpf, eBird regional reviewer for Antarctica and the High Seas, describes how he became an eBird reviewer and his long-term efforts to improve eBird data quality in the High Seas.

eBird Reviewer Spotlight: Michael Schrimpf

I’ve been interested in science and wildlife from a young age, but I didn’t really get into birding until college. I didn’t have as much hands-on experience with natural history or wildlife watching as some of my peers, so I wanted to simply get outside and observe things. Birds captured my attention more than anything else, and my interests in aquatic and marine ecology eventually drew me to studying seabirds.

How did you become an eBird reviewer?

At one point in my career, I began working on ships that made open ocean crossings, taking them beyond the 200 nautical mile limit from land where the “High Seas” eBird region begins. There wasn’t anyone assigned as the eBird reviewer for the High Seas at the time, so during an email conversation with the folks at Cornell they asked if I would be willing to help. I loved using eBird, so I decided to take it on! A few years later, once I began studying Antarctic birds for my PhD, I also took on reviewing Antarctic records.

Much of Michael’s research takes place traveling to and from the Antarctic Peninsula © Michael Schrimpf

What work do you do as an eBird Reviewer?

Like other reviewers, I regularly communicate with users to help them make sure their records and checklists are accurate. There are some aspects of eBird review for the High Seas and Antarctica that are unusual, because birding in those regions is a bit different. Almost all the checklists I review are collected from people standing on the deck of a moving ship or visiting a seabird colony on an Antarctic cruise. A big part of my reviewer role is at the level of the checklist, helping users to record their birding effort correctly. For example, before the introduction of the eBird Mobile App, eBirders on ships often would not have very precise data on exactly where their checklist was located. Having a precise location from a device’s GPS is much more useful.

What is an eBird filter? How do they work, and what do you do to maintain them?

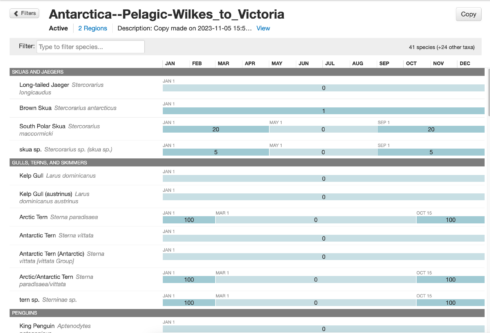

An eBird filter is basically a list of how many individuals of each species should be considered “rare” or unusual for a given region on a given day. Every record is automatically compared to these limits when the checklist is submitted. This is how eBirders are alerted to the fact that they have entered something unusual, and it’s what allows reviewers to easily see which records should be looked at more closely in their assigned region.

Many reviewers also serve as filter editors, and we have an interface which allows us to adjust the limits using our knowledge of bird distributions and seasonal patterns (learn more about filters here). It’s also important that we revisit those filters on a regular basis: as we learn more about species distributions, and as bird communities change, we adjust those filters accordingly.

Setting the limits is not an exact process—I generally ask myself: “how likely is it that someone would encounter this many individuals during a ‘normal’ birding session, and how easy is it to identify that many individuals?” Sometimes, even when you’re within a species’ normal range, there are birds that are so tricky to identify it makes sense to have documentation for most sightings.

The filter interface of eBird that reviewers use to set expected numbers of each species at different times of the year.

You have been reviewing eBird data from the High Seas for many years–can you explain how the process used to work back when there was just a single filter?

The High Seas region has always been an odd world within eBird. The filter system was designed to use a very fine-scale map of the world’s land-based administrative regions, including countries, states/provinces, etc. So, for example, if you’re birding near the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, in Ithaca, New York, your checklist will hit the automated filter for Tompkins County. If that county didn’t have its own filter, the checklist would hit the next larger category—in this case, New York State.

This works well for most places on land, but not necessarily for the world’s oceans, since that fine-scale map doesn’t extend borders onto the ocean. The birds you see near land are counted on your lists for that region, and eBird designed a “closest point of land” approach for any records within 200 nautical miles of shore. So for a checklist located 199 nautical miles from the West Coast of the U.S., with the closest point of land in Humboldt County, California, those birds would show up on the user’s Humboldt County list and be checked against the Humboldt County filter. If it’s 201 miles from shore, the list falls into the High Seas, a single region that wasn’t associated with any polygon on the internal map. Think of it as sort of a base layer that would catch anything not caught by another filter (and since every country on land was covered, the only uncovered region would be the High Seas).

Because that blank base doesn’t have internal divisions, it could only have a single filter. So, as the High Seas reviewer, I could set limits appropriate for the Southern Ocean, the Tropical Pacific, or the North Atlantic Ocean…but only one of these regions at a time (and whatever limits I chose would be applicable to the entire world’s oceans!). This meant that either we could just let everything through unfiltered (which would fail to catch a lot of mistakes), or many records would get flagged as “rare”, even though the birds were relatively common. We chose the latter, and just dealt with those records as best we could. But that resulted in a large backlog of records waiting to be reviewed and much confusion among birders trying to eBird their sightings from ships.

You recently led the creation of new pelagic filters in eBird. Explain how the new pelagic filters were created. Why is the implementation of pelagic filters so important?

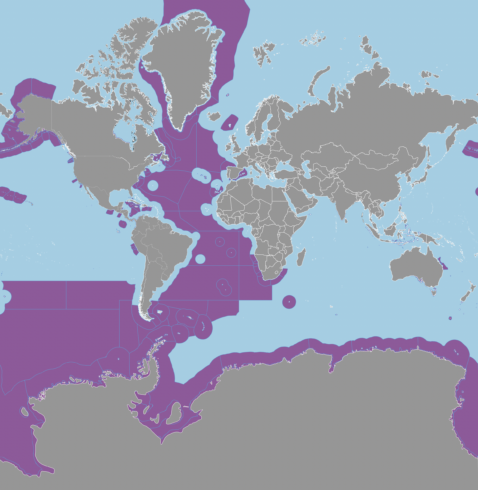

Thanks to my current postdoctoral fellowship, funded through a partnership with Viking Expeditions, I was able to devote the time necessary to create a map that splits the ocean into several hundred different pelagic regions. Working with the eBird technical staff, we found a solution that would allow any checklist on the ocean to keep the same assignment to region as before (i.e., that checklist associated with Humboldt County will still show up on the user’s Humboldt County list), but this new map will also allow the Humboldt County reviewer to produce a separate filter for the pelagic waters between ~10 nautical miles from shore out to 200. And then, once you’re in the High Seas, there will be region-specific filters for different areas. Now that we have the map in place, we are working on filling it in with filters. That will take some time, but it will be worth it.

Michael’s work will fill in the world’s oceans with eBird filters. Offshore filters currently active are shown here in purple.

This will be revolutionary for the High Seas because we will finally be able to have multiple filters within each ocean basin. It will also really help coastal reviewers: before, each filter for a coastal region also needed to cover any seabirds seen dozens of miles offshore, where bird communities are generally very different from nearshore areas. Now, seabirds that are only rarely seen from a land-based seawatch can be properly flagged as rare when reported from shore, but not when seen on a pelagic day trip out to deep water.

It should allow reviewers much finer control over which records they spend their time reviewing and will provide eBirders much more precise lists in the field, so they know which birds will require additional documentation.

What challenges are associated with implementing pelagic filters?

Perhaps the biggest challenge was aligning these new “coastal” (i.e., between 10 and 200 nautical miles) polygons with the “closest point of land” rule that eBird has always used for separating pelagic checklists into different regions. Essentially, there isn’t a good way to do that for the type of map we had to work with. So, I devised a system to approximate those divisions. It isn’t perfect, and it required a lot of tedious work, but it will be a big improvement over what we had before.

In addition to pelagic filters, I understand you helped Team eBird with some other high priority areas on land. What were those and why were they important?

Yes, in many parts of the world, the administrative boundaries created by humans don’t do a good job of also dividing bird communities. This often occurs among island groups, in remote places with very large regions, and along elevational gradients. There were already some of these extra polygons built into the eBird map, but each one requires time to produce and integrate into the larger database. Since we were going to be updating the map, we figured it made sense to get as much of these added as we could with the time available. I managed to complete subdivisions for Colombia and the Brazilian Amazon based on biogeographical regions, create a much more natural subdivision of Alaska, and separate many islands throughout the world. Indonesia was particularly important, since it is a center of avian endemism but the geopolitical regions were completely inadequate for defining bird communities; the new system of island-group polygons and filters has already been implemented and the records have been aligned (thanks to the efforts of reviewer James Eaton). I hope that more appropriate filters in the other areas will aid local reviewers in improving the quality of eBird data in those regions as well.

How are you hoping that the new pelagic filters can help your research interests on the High Seas?

I have believed for years that eBird will eventually transform our ability to understand seabird distributions on the ocean, much as it has our ability to study birds over land. Before we get there, we need two things:

- Better quality controls on the data submitted from birders on ships

- Many more checklists from pelagic regions

I know that these filters will make it easier for us to review pelagic records. My hope is that these improvements in the experience of using eBird on the ocean encourages more people to submit more checklists.

The Cape Petrel–sometimes known as the Pintado Petrel–is a striking bird of the Southern Ocean and can often be seen following ships. It’s one of Michael’s favorite birds. © Michael Schrimpf / Macaulay Library

What can eBirders do to help the review process?

Please take the time to leave detailed comments on your checklists, whenever possible. Providing good documentation on rare birds is important. If you have a photo (even a poor-quality one) consider uploading it. But many seabirds are very difficult to photograph—that’s fine. Simply leave a comment about what field marks you were able to observe and how you ruled out other, similar species.

Many people also don’t appreciate how useful the checklist comments can be—especially on pelagic lists. If you leave a note about what vessel you’re traveling on, what the conditions were like, etc., it gives us a much better sense for the context of a sighting. That also goes for checklists on land—if I’m at a local park, I will often note whether I walked along the trail on the ridge or along the lake. That reminds me of what I was doing and gives the reviewer better information to assess any rare sightings.

Anything else you’d like to share?

I want to send huge thanks to all the eBirders who have been patiently submitting pelagic checklists over the years when they were faced with a very annoying filter experience. Hopefully things will go much smoother now, and we’ll be able to document the world’s seabirds everywhere!